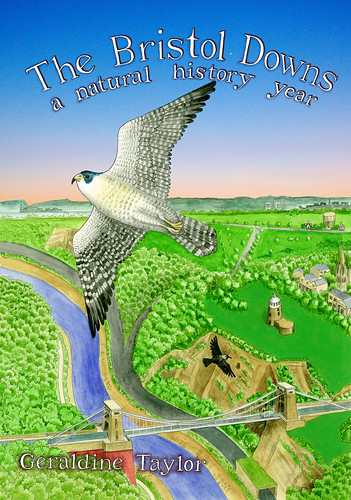

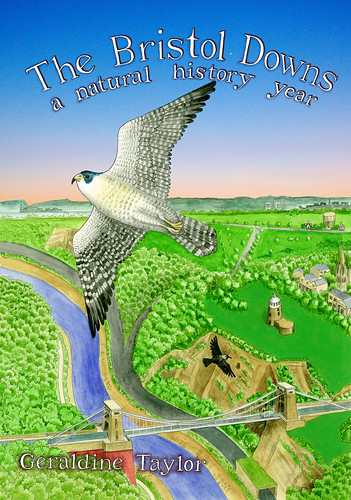

I live right next to the Downs in Bristol, and I was going to write something about them in my blog, but thought that, if you didn't know the area, a bit of explanation might be useful. So here is the introduction to the geology and history of the Bristol Downs that I wrote for this book

The Bristol Downs: Geology and History

The Bristol Downs are part of a limestone ridge which extends north-eastwards from Clevedon. It was formed by sedimentation and deposition when a tropical sea spread over the area during the early Carboniferous period, 354 million years ago. Fossils of marine creatures can be seen where the rock is exposed. During the Hercynian period (about 290 million years ago), when the ancient continents of Laurasia and Gondwana collided, this rock was folded and pushed up into mountains. It was then eroded, deposited upon, uplifted and again eroded until the present surface was once more exposed.

The Gorge was created during the Ice Ages which have come and gone over the last two million years. The Bristol area wasn’t glaciated, but an ice sheet advanced from Ireland up into the Bristol Channel, and it is probable that the Avon cut its way through the Downs because it had been impeded in its original westward flow through Ashton Vale and beyond by this advancing ice front. In the interglacial periods, animals such as bears, elephants, horses, rhinos and hyaenas inhabited the area. Remains of these animals were found in a quarry in Durdham Down in 1842; today part of this discovery (hyaena and elephant bones) can be seen at the City Museum, along with some stone tools of our ancestors, showing that they too were present. The Downs would have been covered with mixed woodland, except in the steeper and rockier areas which would have been colonised by grasses and scrub, much as they are today.

Tree felling began as long as 4000 years ago, and there are field systems evident between Ladies Mile and the Zoo Banks. During the Iron Age, the Dobunni tribe built a hill fort on Observatory Hill, which, together with the two forts on the Leigh Woods side of the Gorge, dominated the river. The Romans in turn built villas in the area, and the road which they built, linking Bath with the port of Abonae (Sea Mills), can still be traced near Stoke Road. The Saxons established grazing rights on the Downs and left boundary stones from Walcombe Slade (Black Rock Gully) to the Water Tower. By the time of William the Conqueror, The Domesday Book of 1086 records the Manor of Clifton as having a population of thirty, of whom half were farm labourers. The Downs provided grazing for the commoners of Clifton and Henbury, and land was leased by the Lords of the Manors for quarrying, lead mining, and limekilns.

The Downs witnessed some turbulence over the centuries. The Royalist army grouped here before taking the city in 1643, and then the Parliamentarians did the same thing two years later. For centuries this was not an area to cross after nightfall because of the footpads and highwaymen, who, if caught, were suspended from the gibbet at the top of Pembroke Road - or Gallows Acre Lane as it was known until the 1850s. With the advent of turnpikes, a tollbooth was installed at the top of Bridge Valley Road in 1727, and then attacked by rioting miners. More recently, troops were stationed here during both world wars, and the Second World War saw the erection of stone obstacles to prevent the landing of enemy aircraft, the tethering of barrage balloons, and the positioning of an anti-aircraft battery at the Dumps. With the arrival of American troops, the Downs were used as a vehicle assembly area in readiness for D Day, and wild flowers flourished between tanks in this temporary respite from mowing.

More of a threat to the Downs, though, was encroaching development. Clifton became a fashionable place of resort with the development of Hotwells as a spa in the late 17th century. John Evelyn described a hunt for Bristol Diamonds (quartz geodes) in 1654:

What was most stupendous to me, was the rock of St Vincent, a little distance from the Towne, the precipice whereof is equal to any thing of that nature I have seene in the most confragose cataracts of the Alpes: The river gliding between them after an extraordinary depth: Here we went searching for Diamonds, & to the hot Well at its foote….

Although development faltered with Hotwell’s decline, by the 19th century it had again revived with the expanding and affluent middle classes seeking to escape from the noxious industrial heart of the city in the valley of the Frome to the fresher air of the suburbs near the Downs. .Quarrying, mining, clay extraction and illicit enclosure all caused further public concern at the loss of the Downs as an amenity for all the citizens of Bristol. The City bought Durdham Down from the Lords of the Manor of Henbury and, along with the Merchant Venturers who owned the Clifton Downs, obtained an Act of Parliament to ensure free public access.

Plans were enacted for the ‘beautification’ of the Downs. The Circular Road was built, quarry workings were filled in, and avenues of trees planted. Change also came about by the decline in sheep grazing, which had hitherto kept in check the growth in trees and scrub; it died out on Clifton Down in the 19th century, and effectively ended in 1925 on Durdham Down, although the University of Bristol periodically exercise their commoners’ rights, last grazing their sheep here in 2007. Today, management of the Downs is the responsibility of the Downs Committee and Downs Ranger, and they remain a popular resort for nature watching, kite flying, sports, shows, fairs and the countless other pastimes engaged in by Bristolians.

Good Morning!

ReplyDeleteIt's amazing what you can discover when you start looking. A very interesting introduction.

When are you going to write one of your own?

Good question, Anji ... I thought Dru's intro was the best thing in the book (not counting the illustrations, of course!)

ReplyDelete