As we left town by the Abingdon Bridge, Jules pointed out the old gaol, now being converted into flats; and, on the other side of the road, the Broad Face Inn, apparently so called to describe the appearance of someone who's been hanged. "They once hung an eight year old boy there," said Julie. "It might be the record for youngest person hanged."

We were soon in Dorchester on Thames, a village which enjoyed the lack of through traffic that comes from being in a loop of the river. The abbey was huge, spacious and uncluttered. "I used to sing here," said Jules., "The acoustics are lovely."

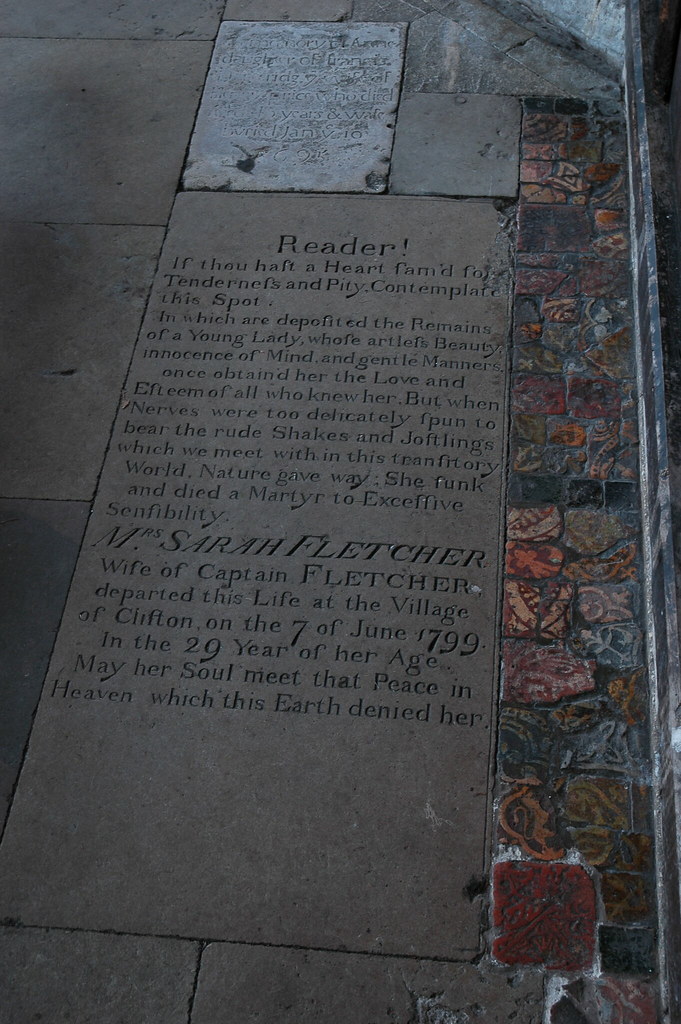

She told us about this tomb. The young woman had killed herself, and unusually for that time was granted a Christian burial. Here's the inscription:

Reader!

If

thou hast a Heart fam’d for

Tenderness and Pity, Contemplate

this Spot

In which are deposited the Remains

of a Young Lady, whose artless Beauty,

innocence of Mind, and gentle Manners,

once obtained her the Love and

Esteem of all who knew her, But when

Nerves were too delicately spun to

bear the rude Shakes and Jostlings

which we meet with in this transitory

World, Nature gave way.

She sunk and died a Martyr to Excessive Sensibility.

MRS SARAH FLETCHER,

Wife of Captain FLETCHER,

departed

this Life at the Village

of Clifton, on the of

June 1799,

in the 29 year of her Age.

May her Soul meet that Peace in

Heaven, which this Earth denied her.

I recalled this tomb being described by Robert Gibbings, the engraver, publisher and author, in his book 'Till I End My Song'. He lived just across the river by Wittenham at the time of writing. Here's what he says.

Sarah Fletcher committed suicide, and according to the custom of that period she should have been buried at a cross-roads with a stake through her heart; but instead her body was given a place of honour in the abbey church. Her husband had not only been faithless to her but had proposed matrimony to a wealthy heiress, living at a distance, and had been accepted. Only at the last moment did Sarah hear of this; only just in time to stop the marriage ceremony did she arrive at the church. Then she returned to the big seventeenth-century house at Clifton Hampden where she had spent her married life and with her handkerchief and a piece of 'small-cord' hanged herself from a curtain rod in her bathroom."

The inscription on the abbey floor might reasonably have

been the end of this unhappy episode, but that was not to be. As time went on

the big house where Sarah had lived and died acquired the reputation of being

haunted. Tenants stayed but a short time: the garden became a wilderness, the

outbuildings fell to ruin. After some years, because of the low rental that was

asked, the place became a school, and though the headmaster had heard rumours

of eerie happenings he said nothing of them to his pupils. ‘There are always

noises in old houses,’ was his answer to his own questionings. Then in the

early hours of a morning the son of that headmaster, a seventeen-year-old boy

who later became the Rev. Edward Crake, heard footsteps in the passage, his

door was opened and he could hear the footsteps in his room; but though it was

moonlight he could see nothing. The unseen walker went from the room and the

door closed.

The boy said nothing to his parents of what had happened nor of similar

occurrences during the night that followed; but on the third night he

determined to leave his door open in order if possible to see the originator of

the sounds. And, as he told the story in later years, ‘I had not long to wait;

the footsteps of someone wearing high-heeled shoes came into my room; they

approached the bed and then retreated. I sprang up and ran into the corridor,

fully lighted by the moon, and there the figure of a young woman was made

manifest to me. She was standing by one of the long windows and she was wearing

a black silk cloak; her hair was bound with a purple-red ribbon. There was

nothing dead about her; she seemed tremendously alive but her eyes were full of

tears.

‘The next day,’ continued Mr Crake, ‘I mentioned what I had seen to one of the

assistant masters and found that I had stumbled on what was common knowledge to

the staff, though any hint of it had been withheld from the pupils. At a

quarter to three every morning restless footsteps wander from the room in which

Sarah Fletcher hanged herself.’

The speaker of these words died in 1915, but others of equal integrity, before

and since his death, have told

of the footsteps they have heard in that house in the early hours of the

morning, and of the woman in a black cloak with tangled auburn hair who had

looked out at them from noonday shadows or been seen in the half-shades of

moontime.